The buzz around self-driving cars has reached a fever pitch over the last decade. Headlines promise a future where autonomous vehicles (AVs) effortlessly whisk people around congested urban centers, eliminating traffic jams, drastically reducing accidents, and freeing up valuable city space. The vision is enticing: safer streets, cleaner air, accessible mobility for everyone, and cities transformed for pedestrians and cyclists—not cars.

But, as with many technological revolutions, the reality is far more complex—and far less rosy than the hype. As a civil engineer deeply invested in how urban infrastructure and transportation systems shape our daily lives, I want to unpack why self-driving cars will, in fact, wreak havoc on cities as we know them. They threaten to deepen existing problems of congestion, pedestrian hostility, urban sprawl, and economic decline—despite the slick marketing campaigns promising the opposite.

Let’s explore some of the technological realities, the urban design context, economic drivers, and potential consequences of AVs.

The Technology Is Real — But Still Far From Ready

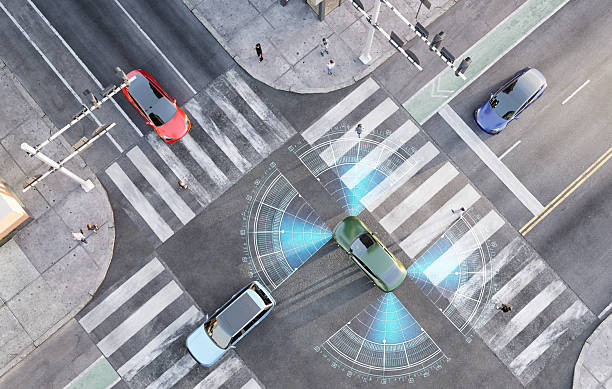

Obviously, self-driving cars exist. They aren’t just science fiction anymore. Companies like Waymo and Cruise operate robotaxi fleets in cities such as San Francisco and Phoenix, allowing users to request driverless cars via apps. But “driverless” does not mean “fully autonomous” in the sense most imagine.

Current AVs still require frequent human intervention. On average, a remote operator must step in every four to five miles to navigate around unexpected obstacles, like construction trailers or confusing turns. This highlights a fundamental problem: the last 10% of automation, the part where the car needs to handle every unusual or rare situation safely, remains elusive. In software development, there’s a saying: the first 90% of the project takes 90% of the time, but the last 10% takes the other 90%. This perfectly describes the enormous challenge in making self-driving cars truly reliable.

Moreover, these vehicles are prone to new, unexpected types of errors. Unlike humans, AVs are “mindless” machines—they follow programmed or learned patterns but can get stuck or behave strangely in complex environments. For example, there have been documented cases of Waymo cars driving in circles, honking at each other late at night, or obstructing emergency vehicles like ambulances and fire trucks.

One tragic case highlights the grave risks involved: a Cruise robotaxi in San Francisco struck a woman who had already been knocked down by a human-driven car. The robotaxi failed to recognize that the woman was trapped underneath it and dragged her further. This accident, although unique, is a chilling reminder that AVs can create new, deadly hazards—not just eliminate old ones.

Public Resistance: The Human Factor

Despite the technological advances, many urban residents are deeply uncomfortable with AV testing in their neighborhoods. Groups like Safe Street Rebel have documented instances of autonomous cars breaking traffic laws—running red lights, blocking intersections, cutting off pedestrians, and parking illegally in bike lanes.

In a telling protest called the “Week of Cone,” activists exploited the cars’ programming to avoid traffic cones by placing cones on their hoods, effectively immobilizing the vehicles. This demonstration highlights another problem: AVs operate within narrowly defined rules and struggle with the unpredictability of real-world urban life.

Cities have become unwilling guinea pigs for billion-dollar tech firms racing to deploy imperfect technology, with residents voicing safety concerns. But regulatory frameworks lag behind the technology, allowing self-certification of safety and limiting police powers to hold companies accountable.

Economic and Political Pressures: Why AVs Are Pushed So Hard

Hundreds of billions of dollars are flowing into AV development. This massive financial pressure pushes companies to prioritize rapid deployment over safety or comprehensive urban integration.

The Silicon Valley mantra of “move fast and break things” has deadly consequences on public roads. Risks to pedestrians, cyclists, and other drivers are often accepted as collateral damage in the race to market dominance.

Meanwhile, governments and regulatory bodies face lobbying and pressure to accommodate AV companies. This can lead to a permissive environment that favors rapid rollout, and therefore creates a problem. If AV firms push for fewer restrictions, the rules become more lenient, this leads to less oversight, often at the expense of public safety.

The Urban Design Reality: AVs Inherit Broken Roads

One of the biggest blind spots in the AV conversation is the flawed urban infrastructure they operate within.

Most American cities are designed around cars. We have streets and roads built for high-speed vehicle travel but crammed into narrow corridors with frequent intersections. These environments are deadly for pedestrians but remain prevalent.

In Tempe, Arizona, an autonomous Uber vehicle hit a woman walking her bike at night, failing to recognize her correctly and stopping too late.

This accident was not just a failure of technology but of infrastructure that prioritizes cars over people.

Roads with higher speed limits certainly have higher chances of reckless driving. AVs inherit this unsafe urban fabric, and no amount of fancy sensors can fully compensate for fundamentally hostile environments.

Safer Streets Come From Design, Not Just Tech

Research is clear: the most effective way to reduce traffic fatalities is not through autonomous vehicles but through better urban design and policy.

Take Sweden’s “Vision Zero” program, which aims to eliminate traffic deaths through a combination of lower speed limits, road redesigns, and strict enforcement. If implemented across the U.S., Vision Zero could reduce fatalities by over 80%.

But this requires political will to reduce car speeds, restrict vehicle access, and prioritize pedestrians and cyclists—moves that clash with a strong car culture and automotive industries.

Ironically, AV companies have little incentive to promote these changes. Their business model depends on widespread vehicle usage and selling expensive technology—not on fundamentally rethinking urban spaces for human-scale mobility.

The Inevitable Arrival—and Its Complex Consequences

Despite protests and glaring safety concerns, self-driving cars are likely to become widespread globally.

The money and momentum behind them make this almost inevitable.

But it’s naïve to assume AVs will magically fix congestion, enhance safety, or be seamlessly integrated with human-driven vehicles and pedestrians.

While AVs may statistically reduce some accident types, they will introduce new risks, unexpected accidents, and new traffic patterns that planners do not yet fully understand.

The American Car Culture Lock-In—and Its Global Effects

American cities are heavily car-centric. Even “walkable” cities like San Francisco prioritize cars far more than many European cities. AVs are trained using millions of miles of American driving data, embedding these driving patterns and cultural norms into their “brains.”

Expecting these vehicles to adapt effortlessly to denser, pedestrian-heavy European or Asian cities is unrealistic.

Worse, European cities may face pressure to “Americanize” their streets—widen lanes, increase vehicle throughput, and reduce pedestrian priority—to accommodate AV fleets.

Training Over Programming: The Hidden Danger

Self-driving cars are mostly trained on historic driver behavior, not explicitly programmed for every scenario.

If cities want to implement pedestrian-friendly changes—reducing car lanes, prioritizing transit, or creating car-free zones—AV companies must retrain their fleets to adapt, an expensive and politically fraught process.

The Myth of Reduced Cars and Parking

Some advocates claim AVs will reduce the number of cars and parking demand, freeing up space.

In reality, human behavior is stubborn: most people prefer owning and parking their own cars rather than sharing robotaxis all day.

Without strong pricing mechanisms like parking fees or road use charges, AVs will likely cruise empty around urban centers, adding to congestion and occupying valuable curb space.

Additionally, AVs may not serve disabled or elderly populations well, who often require physical assistance and may not have smartphones or credit cards to book rides.

Worsening Congestion and Sprawl: The Induced Demand Effect

History teaches us that making travel cheaper or easier encourages people to travel more. Services like Uber and Lyft initially reduced costs due to subsidies but eventually raised prices to maximize profits, with vehicle miles traveled rising as a result.

AV robotaxi fleets, subsidized and convenient, will amplify this trend, increasing congestion.

They may also encourage suburban sprawl, as people live further from urban centers and commute longer distances, spending more time in their vehicles.

The Ghost Town Effect: Faster Car Traffic Kills Street Life

A cautionary tale comes from Bamberg, Germany. After a construction project was completed to improve car traffic flow downtown, congestion improved—but within a few years, every shop closed, and the area became a ghost town.

Why? Because people don’t want to linger on cramped sidewalks next to fast-moving cars. This is a lesson for AV advocates: faster vehicle throughput does not translate to thriving urban economies or vibrant street life.

The Future of Streets: Hostile to Pedestrians and Cyclists

As AVs become more mainstream, fences and barriers may have to be constructed to protect pedestrians from high-speed vehicles.

This does extreme, but AV companies will likely lobby for speed limit removals, arguing that computer-controlled cars can handle faster speeds safely. But, high speeds increase the risk and severity of pedestrian and cyclist injuries.

Traffic lights may be replaced with “Autonomous Intersection Management,” allowing cars to flow continuously at high speeds but making crossing on foot or bike dangerous.

Pedestrian bridges might be the only safe crossing method, but these are often expensive, inaccessible, and unpleasant.

Pollution and Noise: The Hidden Costs

Electric AVs reduce exhaust emissions but don’t solve pollution from tire, brake, and road wear.

Heavier, faster cars cause more particulate pollution, which harms respiratory health.

Noise pollution, mainly from tires above certain speeds, creates stress and health problems.

Cities like Oslo with many electric cars still face serious road noise issues.

AVs, burdened with electronics and driven faster, can worsen air quality and noise near highways and city streets, making these places toxic and unlivable.

The Corporate Control Trap

If AVs dominate city streets, public transit, bikes, and walking will be pushed out.

Travel will be privatized, forcing people to pay AV companies for every trip, allowing prices to soar.

This privatization could fragment cities into islands separated by AV highways filled with noise and pollution.

A Better Way: Lessons from Utrecht

Not all cities need to fall into this trap. Utrecht, Netherlands, took an alternative approach.

Similar in size to many North American cities, Utrecht rejected car-centric planning decades ago.

They transformed highways back into canals, created pedestrian-only shopping districts, and built excellent public transit and bicycle infrastructure.

Car volumes and speeds are low, making walking and cycling safe and enjoyable for all ages and abilities.

No expensive AV technology is needed for this success—just political will to prioritize people over cars.

Conclusion: Prioritize People, Not Cars or Technology

The hype around self-driving cars echoes old promises made by the automobile industry—like General Motors’ 1939 Futurama exhibit, which predicted traffic-free cities with futuristic highways. Instead, highways created sprawling, car-dependent cities with pollution, traffic, and dead urban cores.

Unless we rethink urban design, regulate carefully, and limit car access, AVs will repeat history’s mistakes on a new, automated scale.

As civil engineers and city planners, we must focus on creating safe, walkable, bikeable, and transit-friendly cities—not just shiny tech solutions.

The future should be about fewer cars on our streets, not smarter cars.

Because at the end of the day, people buy things—not cars—and vibrant cities are built for people, not machines.

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter: Stay updated with the latest insights, tips, and innovations in civil engineering.

- Check Out These Must-Read Resources:

- A comprehensive book on civil engineering to enhance your understanding of structural design and construction techniques.

- A captivating book about the lives of great civil engineers, showcasing the pioneers who shaped the modern world.

- A practical project inspection checklist—an essential tool for every engineer involved in site supervision and quality control.

- Dive into the genius of the Renaissance with our recommended book about Leonardo da Vinci, exploring his contributions to engineering and architecture.

- Don’t miss our field notebook and journal, designed specifically for civil engineers and architects to document projects, ideas, and on-site observations

No responses yet